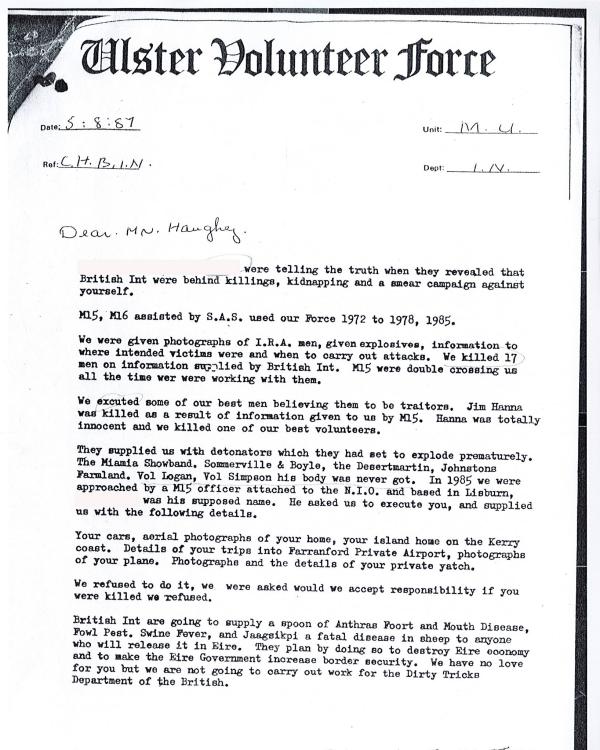

UDA checkpoint, 1972

Gunrunners

Throughout the Troubles and even decades before, Irish republicans used bombings as a practical means of attacking the British and as a form of kinetic propaganda. Bombs conveyed a number of advantages to the user. They could be assembled in relative safety by dedicated specialists and delivered with minimal hazard to the operator. They offered maximum return on a minimal investment – a single blast could result in hundreds of thousands, even millions of pounds of damage, with attendant media focus. Loyalists may have been relative newcomers to the field of explosives compared with republicans, but their involvement with firearms and gun smuggling pre-dates the formation of even the “Old IRA” of the days of Collins and flying columns. Moreover, the gunrunning schemes embarked upon by the militants gathered around Sir Edward Carson, those who signed the Ulster Covenant of 1912 and subsequently formed the Ulster Volunteer Force in opposition to the Third Home Rule Bill, were to have a fateful effect on the course of British and Irish history.

The importation of tens of thousands of rifles by the UVF on-board SS Clyde Valley via Larne in 1914 is undoubtedly the most celebrated episode of loyalist arms smuggling, but there had been piecemeal and sporadic attempts to bring guns into the country over the preceding decades, usually coinciding with efforts by Home Rule proponents to introduce a measure of self-government to Ireland. After the efforts of the Parnellite Irish Parliamentary Party paid off with the drafting of the first Home Rule bill in 1886, scores of rifle clubs sprang up across Ireland and Ulster in particular as Unionists put out a call for “20,000 Snider rifles in good order, with bayonets”. Similar schemes followed a second attempt to bring in Home Rule in the early 1890s. One figure involved in early smuggling efforts around this period who was later to prove a pivotal figure in Ulster gunrunning, and whose name has become legend amongst those who venerate these icons of early loyalist militancy, was Frederick Hugh Crawford.

The eldest of four brothers from a family of ancient Presbyterian colonist stock, it was Crawford who as UVF Director of Ordnance masterminded the Clyde Valley operation, but his involvement in importing arms to equip the enemies of the third Home Rule bill pre-dated this appointment. In 1913 Crawford, posing as an American businessman named John Washington Graham, managed to purchase six Maxim guns from Vickers at the then not-inconsiderable cost of £300 each, his persona proving robust enough that he was even able to test-fire the machine-guns at Woolwich prior to their being shipped to Belfast disguised at musical instruments.

In his meticulously-detailed Carson’s Army, Timothy Bowman contextualised gunrunning by the nascent UVF by drawing attention to the oft-overlooked shooting culture which then thrived. Target shooting was a national pastime for Edwardian Britons. Country pubs were often equipped with gallery or pipe ranges, some of which survive today, where drinkers could while away an afternoon target shooting with .22 rifles. Ireland had a particularly well-regarded national shooting team which competed for various trophies at Bisley camp, the mecca of UK target shooting. More pertinently, firearms laws were liberal, even lax, by today’s standards. Any private citizen of good character could walk into one of the thousands of private arms dealers of the day and equip himself with any number of military-type rifles, revolvers, or pistols. Even belt-fed machine-guns and other fully-automatic weapons were not prohibited by law until 1936. A steady flow of guns arrived in Ulster by such means: 24 Martini-Henry rifles and 1,000 rounds of .577/450 ammo in December 1911; 1,188 Martini-Enfields in November 1914 by RJ Adgey, who imported thousands of surplus rifles through his pawnbrokers and second-hand firearms dealership. Guns were sourced from vendors in high and low society. The Earl of Lanesborough purchased 175 Martini-Enfield rifles from Harrods Department Store for delivery to the UVF in Enniskillen.

The numbers of weapons involved represented a mere trickle to the leaders of an organisation endeavouring to arm 100,000 pledged volunteers, but compared to what their latter-day equivalents were able to achieve it was a deluge. More open markets, less (or non-existent) governmental and international oversight of the arms trade, and wider support from unionist society were all factors in this, the latter in particular. The upper and upper-middle classes were able to use their connections in society and trade to expedite deals, establish contacts domestic and overseas, and help bring in arms, something that their latter-day working class equivalents were unable to fully replicate, aside perhaps certain members of Ulster Resistance.

The ruses and schemes used to conceal the true nature of the shipments coming into Ireland would however have been familiar to the UVF and UDA of 70 years hence. Barrels of “bleaching powder”, their seams packed with farina (a type of starchy wheat powder) so as to “leak” convincingly when offloaded, baize-covered crates of “musical instruments” and “furniture”, steel cylinders marked as industrial filters, and bogus consignments of “cement” and “pitch” destined for phantom construction firms were all among the disguises employed by resourceful loyalist gunrunners. Front companies were established at both ends and sometimes vital intermediate points of smuggling routes, such as John Ferguson & Co. set up with the assistance of Conservative MP Sir William Bull (another example of the original UVF’s wider support base). Involved in various schemes throughout this period was Fred Crawford, whose tireless and energetic efforts to arm the UVF, while not always successful – a caper involving a Maxim gun at a German Army range outside Hamburg ended in farce with Crawford literally making a run for it – did much to sustain support for armament which at times showed signs of flagging.

In spite of the myriad and often ingenious means used, aided by the reluctance of HH Asquith’s Liberal government to wholeheartedly combat unionist smuggling in spite of its sponsorship of Home Rule, by late 1913 the UVF was far from well-equipped. A significant number of its guns had been seized by the authorities while in transit, a major setback taking place when 4,500 Vetterli M1870/87 rifles were impounded in London by the Metropolitan Police under the Gun Barrel Proof Act of 1868. Under-armed local-level UVF units reduced to drilling with wooden rifles pressed for action. A major injection of arms was required to transform it from a theoretical into a substantive force.

The Clyde Valley episode has been recounted in great detail in many other sources, most notably ATQ Stewart’s The Ulster Crisis (where it forms the centrepiece of the book) and Guns For Ulster by Crawford himself, so only an overview will be provided here. The bare facts of the case involve the transit of 25,000 rifles plus 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition from Hamburg to landing sites in Larne, Bangor, and Donaghadee, the enterprise, codenamed Operation Lion, being masterminded by Fred Crawford. The arms were supplied by Bruno (or Benny) Spiro, a Hamburg arms dealer dubiously described as an “honest Jew” by Ronald Neill in Ulster’s Stand for Union. Spiro gave Crawford a choice of several deals of differing makeups, the one accepted consisting of 10,900 M1904 Steyr-Mannlichers and 9,100 Mauser Gewehr 88s. 4,600 Vetterlis whose shipment had been delayed due to British government action would also make the journey, along with 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition. The price was £45,640. Sir Edward Carson was aware of the plot and gave it his blessing with the words “Crawford, I’ll see you through this business, if I should have to go to prison for it”.

Vetterli rifle imported by the UVF. Credit: Imperial War Museum.

The epic journey taken by the munitions – through the Kiel Canal into the Baltic, around the Jutland peninsula, across the North Sea, stopping at Great Yarmouth and the Welsh coast, and a ship-to-ship transfer at Tuskar Rock off Co Wexford – was a pre-war escapade to match the best of Buchan (if not Childers!). After 22 days the shipment reached Ulster on the 24th of April on-board the coal vessel Clyde Valley, renamed Mountjoy II for the operation. Amidst decoy landings and deliberate misinformation the UVF then essentially seized the ports of Larne, Bangor, and Donaghadee where the arms were landed in three stages before distribution to UVF battalions across the nine counties.

The rifles disgorged from the holds of the Clyde Valley and via other clandestine routes were certainly prodigious in number, but they were not necessarily all of the highest quality and many could in no sense be said to represent the state of the art. The Martini-Enfields, a .303 conversion of the single-shot Martini-Henry of the Zulu Wars era, were intended as a stopgap weapon for second-line troops and the like. Although powerful enough, their rate of fire was decidedly lacking and like all British Army rifles prior to the SMLE they suffered from accuracy problems due to inadequate factory zeroing which would have required attention from UVF armourers. Lee-Metfords were considerably better, with a large for the time magazine capacity and a bolt-action which could be operated with great rapidity, but they were long and unwieldy and their rifling quickly wore out using the ammunition of the time. The Italian Vetterlis in particular were poorly-regarded. A report by Brigadier-General Count Gleichen was notably dismissive, remarking that they were “not good, but weedy + weak + only cost 5 francs apiece, including belt and bayonet!”.

In any event the rifles were not needed. War in Europe intervened and as its volunteers enlisted to fight Germany and its allies the UVF put its guns into long-term storage, co-operating with the authorities to ensure that they did not fall into the hands of the Irish Volunteers. It was an irony that the formation of the UVF and its energetic gun smuggling prompted militant Irish nationalism to formally organise and embark upon its own (less successful it has to be said) efforts to arm, and that guns brought into the country to potentially be used against British soldiers enforcing the will of parliament ended up in their care. Over coming decades the guns – a considerable nuisance to those charged with their storage and upkeep – were gifted or sold off piecemeal to various concerns including the newly-formed Ulster Special Constabulary, Belgium, South Africa, the Home Guard, and even the Sea Cadets.

The gunrunners of 1911-14 provided a source of inspiration to the leaders of the loyalist paramilitary organisations of the post-1969 conflict. The walls of the Eagle, the modern UVF’s headquarters, are adorned with images of fallen volunteers, the faces of those “killed in action” such as John Bingham, Charlie Logan, and Aubrey Reid. Superseding all though is a framed portrait of Sir Edward Carson, ratifier of Crawford’s Hamburg scheme, whose inscrutable countenance gazes down upon the room like St Peter in a Russian Orthodox shrine. But without the high-level connections possessed by the Ulster Volunteers of old the UDA and 1965 UVF could never hope to match the feats of their forebears – their example was an approximate model, not a template.

Early Days

The first shots of the Troubles fired in Belfast rang out in August 1969 when the OC of the IRA in the city, Liam McMillen, ordered his men out onto the streets with instructions to create disorder so that they might relieve pressure on nationalists in Derry who were then engaged in pitched battles with a concentrated force of RUC. The petrol bombing of police stations on Hastings Street and the Springfield Road quickly took place, followed by a car showroom in Conway Street between the Falls Road and the Shankill. The situation worsened over the next few days, with republicans exchanging fire with the RUC in Shorland armoured cars, culminating in the burning of Bombay Street by loyalists and B Specials after a street battle with nationalists. As violence worsened and British troops appeared on the streets IRA Belfast Brigade adjutant Jim “Solo” Sullivan, in his guise as chairman of the Belfast Citizens’ Defence Committee, told the Belfast Telegraph that nationalists and republicans were in possession of “automatic weapons, revolvers, and rifles”.

In the sustained communal violence of 1969-71 loyalists found themselves badly outgunned by the IRA and republican vigilantes. There were certainly weapons in working class Protestant areas – Constable Victor Arbuckle was shot dead in October ’69 during rioting on the Shankill by a “sniper” armed with a .22 rifle – but nothing particularly formidable, at least in comparison to what the IRA was able to field even at this early stage. Ardoyne IRA volunteer Martin Meehan described “bucket loads” of arms as…

[…] coming from everywhere, mostly from old republicans who had buried gear in the twenties, thirties, and forties. They were in perfect working order. We couldn’t cope sometimes with the amount of gear coming in. It was unbelievable. There were sub-machineguns, old .303 rifles and ‘Peter the Painters’ [Mauser C96s] – a pistol on a sort of a handle to give you a better grip than an ordinary pistol would.

On the 27th of June 1970 the newly-emerged Provisional IRA used Orange parades as a pretext for launching well-prepared attacks on loyalist marchers in east and west Belfast. It engineered a confrontation around St Matthews Church in the Short Strand, opening fire from within the grounds of the church itself. Contrary to the well-established republican version of events, it was Protestant civilians rather than UVF gunmen who suffered that day. Two men were shot dead and dozens injured, including a number of women, in addition to three dead in Crumlin Road. According to local accounts it was only later that loyalists managed to arm themselves with two handguns, plus an elderly Mauser Gew88 and a Martini-Henry rifle from the days of the original UVF, and return fire. Witness to the events of that evening was a young David Ervine, who was deeply affected by what he saw:

I can remember a guy getting shot and it wasn’t like the movies. The guy got shot in the hip and, and the blood spurted about three feet, and I just thought ‘Jesus’ you know, you saw John Wayne and there was a stain. That just wasn’t the way the world worked […]

Not only did the sole IRA casualty come about after one of its own gunmen, believed to be Denis Donaldson, lost control of a Thompson SMG, but it later transpired that the fallen “Oglagh”, Henry McIlhone, was not connected to the organisation in any way. Over the next three decades his family campaigned to have his name removed from the IRA honour roll, and were ultimately successful. But at the time the “Battle of St Matthews” was hailed as a great victory for the newly-blooded PIRA, immediately establishing their credentials as modern-day Defenders.

An arms dump found in October 1972 shows some of the antiquated weapons loyalists were equipped with at the time – Martini-Henrys, Martini-Enfields, and Steyrs. One rifle was dated “1893”. A homemade pistol marked with “For God and Ulster” and “UVF” was also found.

These events also helped to convince the loyalist vigilante groups which were gradually coalescing into what would become the UDA of the need to arm, but progress was slow and not helped by some of the so-called leadership at that time:

There was real atmosphere there at that time, that something was going to happen and we wanted the gear to defend ourselves. The boss kept saying it was stashed and when the time came, it would be there and we were saying ‘let’s see the weapons’. Eventually he brought some stuff up in the boot of his car and it was nothing. A couple of old rusty pieces.

Some managed to arm themselves with whatever relics and knick-knacks came to hand, weapons like “Steyrs, the odd Webley or Martini-Henry; a lot of the lads had been in the army and had hung on to something”. Sammy Duddy, a member of the early Westland Defence Association and later press officer for the UDA, recalled the dire state of their arsenal at that time in conversation with Colin Crawford:

[…] we had no guns. The IRA had automatics [machine-guns], high-velocity sniper rifles, powerful pistols, the lot, but we had fuck all. There were virtually no guns on the loyalist side. The only weapons we had were baseball bats and I just thought to myself, ‘what the fuck are we going to do when they [the IRA] come in with their machine-guns? Throw bats at them?’

Duddy spoke of vigilantes finding themselves in a situation where men manning barricades were reduced to carrying water pistols painted black, earning them the derisive nickname of “The Water-Pistol Men”. Like the UVF of 1913 the UDA was, on paper at least, a large and formidable body of men comprising tens of thousands, but without arms its capability was only speculative. Again, as in 1913, grassroots activists and ground-level units began agitating for more than imitations. It was clear that the organisation’s leadership would have to do something.

By early 1972 the UDA – although it had traded shots with the IRA in a long-range gun battle the previous December – was still woefully under-equipped for a campaign of defence never mind the savage retaliatory violence it later became known for. In February a solution seemed to be at hand. The November before an approach had been made to an assistant at a Belfast firearms dealership – Guns and Tackle – owned by John Campbell, a former B Special. It had been made at the behest of Charles Harding-Smith, leader of the Woodvale Defence Association and overall chairman of the UDA, and concerned the viability of purchasing rifles “under the counter”, a figure of £50,000 being mentioned. In February Campbell contacted a manufacturer of gun holsters who in turn passed him on to a person purported to be a Scottish arms dealer. This figure, hearing that Protestants “had had their noses rubbed in it for two or three years and were not going to take any more”, intimated that he and a contact of his in London would be able to meet the needs of the loyalists. After preliminary talks between the UDA party and the dealer at a pub in London’s West End, a final meeting was arranged to take place at the Hilton on April the 29th, using a Vanguard rally in the capital that weekend as cover. John White, later to find notoriety as one of the killers of Senator Paddy Wilson, travelled over with Harding-Smith and a number of others: “We were going to look at final shipment and work out the logistics of taking control of the arms and passing on the money”. Negotiations had progressed to the point where talk now was of an order in the region of £100-250,000, involving assault rifles, pistols, and submachine-guns. The UDA were on the verge of a major coup which had the potential to transform them from Water Pistol Men into a real army, as Harding-Smith spoke of the next deal being made “government to government”.

As with most things which seem to good to be true, it was. The deal was a set-up and had been from the outset. The Scottish connection turned out to be a policeman, William Sinclair, while his London counterpart was revealed to be a Michael Waller, a member of Special Branch. White and the rest of the UDA delegation were arrested in the foyer of the Hilton, Harding-Smith being picked up later. At their trial in December their lawyer offered the unusual defence of claiming that they were in fact attempting to trace and trap a gun dealer who had been supplying the IRA. Astonishingly this gambit was accepted by the jury, Harding-Smith, White and the others walking free. A number of the other conspirators were jailed, however, among them a former Belfast city councillor and another ex-B Special. None of the men had prior criminal records and the judge accepted good character references. Handing out relatively light sentences, Mr Justice Waller said:

I realise the tremendous emotions which must have been involved to turn you from the behaviour which you had adopted until 18 months ago into contemplating illegal activity of this kind […] it is impossible for us in this country to appreciate the pressures to which people have been exposed in Northern Ireland over the last two years.

Speaking to Peter Taylor 20 years later, John White said “we felt very silly and realised that we had been conned right from the very start. I suppose we were very naive in the way we tried to acquire these arms. But that was to change as we later became more professional as we went along”

The sting had internal repercussions for the UDA which was then in the throes of various power struggles which would not abate until 1975. The organisation had had its fingers burnt, and the supply routes which later developed in Great Britain and Canada were handled more cautiously. Still faced with the need to arm, in the meantime both it and the outlawed UVF turned their attention to a source of weapons closer to hand.

Self-Service: Arms Raids

The problem of supply of weapons, in particular the often limited sources available, has been and remains a perennial issue for guerilla and terrorist movements. The international arms market and the often dubious figures who move among it have frequently proved to be less than reliable, as he Hilton affair amply demonstrated. Expedient homemade weapons may fill the gap in the short term, but even the best examples cannot match the quality of the genuine article. Fortunately for the terrorist quartermaster, there is usually another ready source of modern, high-quality weaponry which may be tapped by those with the will and daring to do so – the armouries of the state forces themselves.

Long before loyalists embarked upon what Gusty Spence euphemistically called “procurement” operations the pre-split IRA were helping themselves to the ready stocks of Lee-Enfields, Stens, Webleys, and Bren guns held by both the British Army and an tArm, the Irish Army. In fact, in the years before American and Libyan arms came on stream this constituted their main source of arms.

In December 1939 during the early days of its sabotage campaign in England the IRA, taking advantage of a weak guard presence, launched a raid on Magazine Fort in Phoenix Park, Dublin which resulted in a haul of almost half a million rounds of .303 ammunition, 612,000 rounds of .45 ACP for use in Thompson SMGs, plus several rifles and a small assortment of military ephemera. The great majority of the ammunition was soon recovered, but the operation was a considerable morale booster for the organisation. From 1951 more raids occured, this time in the “Six Counties” and England. In June of that year Ebrington Barracks in Co Derry was hit, with 20 Lee-Enfields, 20 Sten guns, and a number of Bren and BESA machineguns taken. Six weeks later the IRA targeted the armoury of the Combined Cadet Force detachment at Felstead School in Dunmow, Essex. Although over 100 weapons, including a PIAT anti-tank spigot mortar, were seized, the raiders (including future Chiefs of Staff Cathal Goulding and John Stephenson, later Sean Mac Stiofain) were soon picked up by police along with their haul. Further raids of varying success occured at Gough Barracks in Armagh, Omagh Barracks, RNAS Eglinton near Derry, and Arborfield Army Depot outside Reading in Berkshire.

A common feature of these operations was the use of IRA moles to infiltrate the bases in order to gather intelligence prior to the robberies, just as loyalists would later do in their hold-ups of TA and UDR centres, putting republican claims of “collusion” in a rather different light. A rather self-congratulatory retrospective in An Phoblacht celebrating the 50th anniverary of the Gough Barracks raid breezily recounted how after Sean Garland enlisted in the British Army “a stream of maps, documents, time schedules and even photographs flowed into GHQ for processing”. Several IRA members including a senior intelligence officer even gained access to the base with Garland’s connivance. This constitutes an episode of collusion by any definition of the term, but it is one the republican movement appears prepared to accept, “[keeping] alive the flame of republicanism through to the present time” as it did.

As the first of the modern loyalist paramilitaries to appear, the UVF was unsurprisingly also the first to target military installations and other legitimate sources in its search for arms. After his swearing-in to the revived UVF in late 1965, Gusty Spence was informed that “we were never getting any firearms. We had to purchase our own. We were told to procure and to hold ourselves in readiness”. Funds for weapons would also have to be “procured”:

We bought our own firearms. We garnered funds whatever way we could and I think there was at least one bank done in those days on the far side of the town and I think it was six or eight thousand pounds.

It appears this was the theft of £8000 from a sub-post office on the Saintfield Road, “for further arms to be used against the enemies of Ulster” as an unconfirmed statement to the local press claimed. The disarming of individual members of the state forces, such as the Ulster Special Constabulary, was already a feature even before the conflict. According to Spence:

(the UVF) knew where the B men lived and it was a matter of going in and taking their arms.

Other legal arms could also be taken:

Virtually every bank in Northern Ireland at one time also had a legitimate firearm. I remember as a boy going to get change of thruppence and seeing the big gun sitting on the counter in the bank in Malvern Street. These weapons were withdrawn but it was known where they were kept. The Harbour Police could also be disarmed. The UVF had to have weapons.

Spence went on to state that illegal channels were also used at this time:

I was always pestering this man for firearms and I bought the first Thompson sub-machinegun that was ever seen on the Shankill Road. I paid thirty quid for it and twenty rounds of ammunition. A .45 Webley pistol cost a fiver, which was big enough money in those days for working men.

However the early UVF got hold of its weaponry it soon put it to deadly use. In the early hours of the 26th June 1966, Catholic barman Peter Ward was shot dead and two of his companions wounded upon leaving the Malvern Arms on the Shankill Road. Their attackers were all armed with handguns, including Smith & Wesson and Colt revolvers, and a .45 Colt automatic. During the trial it was alleged that earlier in the evening a UVF meeting had discussed acquiring more arms. Subsequent to the imprisonment of much of the Shankill UVF in the wake of the Malvern Street trial, the organisation retreated into the shadows. During the next few years procurement operations appear to have been seldom and pointedly unsuccessful, such as the 1967 break-in at an army camp in Armagh which yielded only a handful of non-firing drill rifles.

1972 was the year in which Northern Ireland came closest to civil war. A staggering 10,628 shooting incidents took place, roughly 30 each day. In working-class Belfast law and order had broken down almost entirely with several killings – often random and sometimes extremely brutal – occurring daily. Large areas of nationalist Belfast existed in a state of semi-seccession as virtual paramilitary fiefdoms run by the Provisional IRA, the security forces too fearful to venture beyond the barricades into these “no-go areas”. These developments, along with the proroguing of Stormont, greatly stimulated the growth of loyalist paramilitary groups. That summer the Provisional IRA, by then already well supplied with weapons from Irish-American sympathisers in the United States, successfully negotiated the delivery of arms from Colonel Gaddafi’s regime in Libya. Loyalists did not enjoy the advantage of direct state sponsorship that the Provisionals had with Libya and briefly the Dublin cabinet, nor did they possess a well-connected diaspora in the US. Much of their arsenal at this time was made up of antiquated (sometimes dating back to the Clyde Valley shipment) or low-quality firearms. William “Plum” Smith, a founder member of the Red Hand Commando wrote of this period:

We, as Loyalists, didn’t have such impressive connections with the world of armaments [as the IRA]. Our first trawl of weapons looked like something from a WWI museum with bolt-action Steyr and Torino [Vetterli] rifles, shotguns, a few handguns and very little ammunition. The odd Lee-Enfield rifle or Sten sub-machinegun were a luxury […]

A situation in which an aged Lee-Enfield was regarded as a luxury suggests a poorly-armed Red Hand indeed. The need to equip the large number of new recruits with modern weaponry, and to offset attrition due to security force action, triggered a massive spike in the theft of guns from not just military bases but on- and off-duty members of the security forces. Gusty Spence, having escaped from jail at the beginning of July, was involved in reorganising and re-equipping the UVF at this time:

Firearms were most important. If they didn’t have sufficient firearms they had to be procured. This meant raiding for arms and taking on the army to a degree.

Small-scale thefts were already taking place – in May armed raiders struck at the homes of two off-duty members of the Ulster Defence Regiment in Coagh, taking three rifles, two shotguns, and the men’s uniforms – when a spate of robberies targeting military bases began in autumn. The first took place at the headquarters of the UDR’s 10th Battalion on Lislea Drive in the early hours of the 14th October. Having first subdued a lone sentry outside, a group of armed men burst into the guardroom and overpowered the three guards inside. Now in control of the armoury, they took 14 SLRs and a quantity of ammunition before escaping. Although proof of inside assistance was never conclusively established, the guard commander on duty that night was subsequently dismissed after several reliable intelligence reports linked him to the UVF. The robberies targeting individual UDR personnel also made a contribution. Between October 1971 and November ’73 96 weapons were taken from the homes of UDR personnel, including 47 SLRs and 37 pistols, although loyalists were not responsible for all of these thefts.

No doubt emboldened by its success earlier in the month, the UVF’s next raid was far more ambitious. Situated next to a picturesque public park, Kings Park Camp in Lurgan was shared between the Territorial Army Volunteer Reserve and UDR. At around 4:15 or 4:20 AM on the 23rd October members of C Company, 11 UDR and 85 Squadron, 40 (Ulster) Signals Regiments TAVR were on guard duty when a red Ford Cortina containing four men in army uniform drew up to the gate where a lone TAVR sentry was “stagging on”. Moments later guns appeared in the hands of the “soldiers” who, overpowering the hapless part-timer, were immediately joined by another ten raiders. Gaining entry to the base they similarly captured and disarmed the duty guard inside, but in doing so alerted the armourer who locked himself in the armoury, sealing off their objective. Holding a gun to the head of one of their captives, the raiding party pounded on the door and shouted “we’ll kill these men here one by one unless you let us in”. With little choice but to comply, the soldier unlocked the door. The gang quickly began emptying the base’s stockpile of weapons, hastened by the fact that a soldier coming on duty had raised the alarm, transferring them to their cars and an army Land Rover outside. By the time they made their escape they had seized no less than 85 SLRs and 21 Sterling SMGs, plus 1500 rounds of ammunition. As one UVF man later said, “we got so much fuckin’ stuff we didn’t know what to do with it”. If there was any jubilation amongst the UVF team at the scale of the spoils it must have been short-lived: the Land Rover containing much of their captured weaponry quickly developed a fault. They were forced to abandon it in an isolated woodland spot about four miles from the base, near Portadown Golf Course, camouflaging it with branches and foliage. The guns themselves were stashed in a hastily-built hide near the Cusher River.

Having been caught unawares and with all nearby police and army units alerted, the security forces reacted swiftly and efficiently. Roadblocks were set up along all main roads, while local UDR units joined by the RUC and soldiers from the Staffordshire Regiment swept through a 16-mile search radius. They did not have to look for long. First a UDR sergeant found a Sterling lying on the Portadown to Gilford Road, then shortly afterwards the Land Rover and hide were found by another member of the regiment. 63 SLRs, 8 Sterlings, and 800 rounds of ammunition were recovered – the bulk of the UVF’s haul. It was enough for the authorities to declare the operation a success and the Belfast Telegraph front page to crow “Army strike back after gang raid on depot” the next day. In reality the UVF, in spite of their vehicular mishap, had got away with 35 “top-class weapons” (in Gusty Spence’s words) without firing a shot. That they did so was down to their infiltration of the UDR. As a Royal Military Police investigation noted:

It is quite apparent that the offenders knew exactly what time to carry out the raid. had they arrived earlier they may have been surprised by returning patrols and had they arrived later they may have been intercepted by the Tandragee Power Station guard returning from duty. The very fact that all the guard weapons had been centralised and there was only one man on the main gate, a contravention of unit guard orders, was conducive to the whole operation. The possibility of collusion is therefore highly probable [emphasis original]

In fact the conrate (full-time) UDR sergeant on guard duty that night was Billy Hanna, a former Royal Ulster Rifles regular and winner of the Military Medal for gallantry in Korea. Though much has been written about Hanna by amateur and self-published authors – he is variously alleged to have planned the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, to have been the leader of the Mid-Ulster UVF, and an agent for British intelligence – the UVF has consistently denied that Hanna was ever a member of the organisation much less on its Brigade Staff, as his particularly bad Wikipedia profile alleges. Although we cannot take this denial at face value, there is virtually no proof for any of these claims. It is almost certain however that Hanna was involved in setting up the Lurgan raid, and it is known that he was later dismissed from the UDR on account of his connections with loyalist extremists.

After Lurgan the hold-ups continued. At the end of October a loyalist gang broke into an unmanned RUC station in Claudy and took four Sterlings. Unfortunately for the raiders the weapons had been stored without their bolts as a precaution following the previous thefts, rendering them inoperative. However loyalists possessed the ability to manufacture replacement bolts, and had taken spare parts for Sterlings on other occasions. Such safety measures were therefore no guarantee that disassembled firearms could not be restored to working order. A week later two more incidents took place. At 10:00 AM on the 8th November an armed five-man UVF team burst into the small police station in the village of Aghalee near Lurgan and tied up the lone officer on duty, taking his uniform, cap, and Walther personal protection weapon (PPW) before fleeing. One of the gunmen was armed with a Sterling SMG, neatly demonstrating the self-sustaining nature of arms raids. Much more serious were the events which had taken place in Belfast in the early hours of that morning. As a vital part of the capital’s infrastructure, and a prime target for the IRA, the pumping station in Oldpark Terrace was allocated a “key point” UDR guard. During the interval between the changing of the guard shift an armed gang consisting of eight men overpowered the facility’s nightwatchman. With the rest of the group lying in wait, one of them posed as the watchman and let the new guard into the station. The trap was then sprung: all 13 UDR men were relieved of their SLRs plus their allocation of ammo – 260 rounds in all. Once again the raiders were armed with stolen army weapons, this time SLRs.

By now nationalists had become extremely concerned about the spate of successful heists targeting military arsenals and personnel. The Irish News reported that MP Ivan Cooper of the SDLP had contacted Willie Whitelaw to ask him “how much longer the arming of Protestant extremists by the UDR was going to be tolerated”. Referring directly to the pumping station hold-up, Cooper stated that only “imbeciles” could accept the story that 13 armed soldiers had allowed themselves to be surrounded and disarmed, and warned that in the event of civil war or a Whitehall-imposed settlement the UDR would likely side with the loyalist paramilitaries. Calling for the disbandment of the locally-recruited regiment, he said:

The Oldpark Pumping Station farce is one of a number of incidents which have demonstrated undeniable collusion between the UDA and the UDR. The Secretary of State cannot afford to turn a blind eye to this latest incident and the obvious step which he must take in the interests of the entire Northern Ireland community.

In 1972 the UDA was rarely out of the news and as such it took the blame for most of these incidents, but in reality there was no conclusive proof of their involvement. Most, but not all, of these early jobs instead appear to have been carried out by the UVF, and exactly who was responsible for the Oldpark robbery is debatable. But the UDA did carry out a number of operations directed against military installations. Indeed its raids were even more ambitious, as will be seen.

The number of raids on military bases dropped off sharply after this flurry of activity. Security measures at armouries were increased somewhat and sentries were better briefed on what action to take in the event of a hold-up, helping to staunch the outflow of arms. As a then-secret British Army report stated “[s]ubversion in the UDR has almost certainly led to arms losses to Protestant extremist groups on a significant scale. The rate of loss has however decreased in 1973”. 55 weapons were stolen from the army in 1973 compared to 148 the previous year, a considerable drop. Among the incidents which took place were two robberies in mid-Ulster targeting the homes of UDR members in which two Sterlings, each with a full magazine, and a .38 Enfield revolver were stolen. Five days later there was more embarrassment for the authorities. Thursday the 8th was the day on which all of Northern Ireland – in theory, at least – took part in the “Border Poll”, the referendum asking voters whether they wished the region to remain within the UK or not. Almost the entire nationalist electorate boycotted the referendum, with just 6,500 votes cast in favour of a united Ireland. As republicans organised mass burnings of postal votes and voting cards violence was anticipated, and a soldier from the Coldstream Guards was shot dead outside a polling station. Loyalist paramilitaries used the presence of extra guards outside the stations to conduct two arms grabs. The first took place at a polling point in Berlin Street on the Shankill. A delivery lorry blocked off the road to create an obstruction and then a Transit van appeared, seemingly wishing to get past. When a UDR commander approached the vehicle to speak with the van’s driver the front passenger leapt out and shoved a sub-machinegun in his stomach. Another man, armed with a Luger, sprang from the back of the van and held up the two sentries. Eight others followed him and disarmed the guard, taking 13 SLRs in total plus their body armour. One soldier who resisted was thrown into a glass door and slightly injured. The raiders then drove off in the van at high speed. According to an army spokesman “the sentries took no action for fear of the guard commander’s life”. On the other side of the city two UDR men guarding the polling station at St Patrick’s Hall in Dee Street were approached by six men who produced guns and stole their rifles and ammunition. The gunmen escaped in a hijacked Ford Cortina which was later found burned out near Beersbridge Road.

1974 saw a further reduction in the number of military firearms stolen, 25 in total. Queen’s University was the site of the most significant theft when on the night of April the 3rd an armed UVF team attempted to break into the armoury of the Officer Training Corp centre at Tyrone House. They failed to do so but succeeded in disarming the guards of six SLRs, five magazines, and 75 rounds of ammunition. A week later a 26yr old welder from Donaghadee was arrested and charged in connection with the raid. The court heard that he had refused to make a statement or give an account of his movements that night. The arms were not recovered.

Until now the UVF had been the more active of the two main loyalist groups in launching procurement raids, but if anyone doubted that the UDA were inclined to get involved in such activities the next major break-in would have left them in little doubt. In 1975 the organisation carried out what was then the largest ever theft from an army base by loyalists. The scale of the robbery prompted questions in parliament, leading junior Labour defence minister Brynmor John to issue a statement:

At approximately 03:15 on the morning of 16th June a car containing four men dressed in combat clothing drew up at the base of F Company, 5 UDR at Magherafelt, Co Londonderry. The sentry who went to investigate was immediately held up by the men, who were heavily armed. Two further cars then drew up, bringing the total number of men involved to about 10. The guard, consisting of a corporal and six men, were overpowered and tied up. The raiders then broke into the armoury and stole 148 self-loading rifles, 35 sub-machineguns, one General Purpose Machine Gun, three smallbore .22 rifles, 35 pistols, and several thousand rounds of ammunition. The men then escaped with their haul in two Land Rovers, which were later found burnt out about four miles away. The only casualty during the incident was one of the guards who was knocked unconscious.

This was a well-planned and slickly-executed undertaking. Moreover, the minister also failed to mention that the UDA had got away with eight grenades and an 84mm Carl Gustav anti-tank weapon, used by the army to fire inert training rounds into car bombs in order to disrupt their firing mechanisms. But as with the Lurgan raid, success was short-lived. Later that morning the entire haul was recovered by 5 UDR when a 50,000 litre-capacity slurry pit at a farm roughly four miles from Magherafelt was pumped out after a police tip-off. Worse still, the UDA lost the four guns which the raiders had used in their takeover of the camp. Although in the government’s eyes calamity had been averted, Merlyn Rees was roundly criticised by Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe for the failure in security. Once more inside assistance was in evidence: Ronald Nelson, a member of 5 UDR, was later convicted in connection with the raid.

Loyalists did not always have to use force to acquire weapons from the security forces. On rare occasions soldiers or policemen sold arms to the paramilitaries out of sympathy or for base financial reasons. In 1971 a former B Special was convicted of passing guns to loyalists and given a 12-month suspended sentence. Nicholas Hall, a member of 1 PARA, was given a two-year jail term and discharged from the army for supplying the UVF with hundreds of pounds worth of military hardware. He later found notoriety as a mercenary in Angola under the brutal and amateurish command of his associate “Colonel Callan”, real name Costas Georgiou, another dishonoured former Para. In August 1986 a UDR colour sergeant, in spite of the fact that he was visibly drunk, managed to sign out 18 weapons from the armoury at Palace Barracks and then sell them to the UDA for £3,000, less than half their true value of £7,700. The guns included two L4 Bren light machineguns, 11 9mm Browning pistols, a .38 Special Smith & Wesson revolver, plus 17 telescopic sights. He was arrested in Dublin several days later and extradited, leading to a five-year prison sentence. Three years later Browning #BL67A 4931 was used in the killing of solicitor Pat Finucane.

By 1987 major robberies against army bases were thought to be a thing of the past, a feature of the conflict’s wilder early days. Many of the weapons stolen during the 1970s had been recovered, including most of the SLRs, and loyalists were believed to have turned to overseas sources of arms instead. There was therefore great shock when the UDA, with seeming ease, gained entry to the UDR base at Laurel Hill House in Coleraine and carried out another massive arms robbery. Just before dawn on the 22nd of February three armed and masked men suddenly appeared in the base armoury and overpowered four UDR soldiers on guard duty. One man resisted and was knocked unconscious, the remainder were handcuffed and gagged. The gang then spent the next two hours emptying the armoury, loading 144 rifles, two Bren L4 light machineguns, 28 pistols, and thousands of rounds of ammunition into a UDR Transit van. Military radios and binoculars were also taken. The raiders then calmly drove out the front gate.

Once again, such a large theft could not fail to initiate a massive security alert. One of the guards managed to free himself and raise the alarm, and less than an hour later the van was stopped by the RUC 40 miles away on the M2 near Templepatrick. The stolen weapons plus two guns used by the raiders were recovered.

The Laurel Hill raid sparked a political outcry. Secretary of State Tom King immediately ordered an inquiry into the affair, and met with his deputy Nicholas Scott, and Major-General Tony Jeapes, Commander Land Forces, to discuss the break-in. Scott made a statement declaring “these weapons could have caused untold damage in Northern Ireland. We have to congratulate the police on getting them back”, but this did nothing to assuage those who suspected inside assistance. John Dallat, then a local SDLP councillor, called for the closure of the base, saying:

It is obvious that, if a loyalist group can drive up to the front gate of the UDR base, load up virtually the entire arsenal of weapons, using a UDR vehicle, then that base has nothing to contribute to security as I understand the term.

Concerns were raised about “unsavoury elements” having access to government property, while rumours abounded that UDA members had attended drinking parties inside the base. Although both Ken Maginnis and Coleraine deputy mayor James McClure dismissed allegations of inside help, instead blaming a recent reduction in guard numbers, two lance-corporals in the UDR were arrested. Initial reports that the UDA had gained access by cutting the perimeter fence were incorrect: it transpired that one of the soldiers had smuggled in the UDA raiders in the boot of a car, allowing them to surprise the guard. He was jailed for nine years while his accomplice received a two-year suspended sentence.

The procurement raids targeting the security forces were undoubtedly an important source of arms for the loyalist paramilitaries in the early days of the conflict. It gave them access to powerful and reliable hardware at almost no outlay for those bold enough to take on the military inside its fortified citadels. Penetration of the security forces helped. Although individually collusive acts were clearly in evidence in many of the incidents, there is nothing to suggest that this constituted a systematic or officially-sanctioned policy. On the contrary, the raids caused much embarrassment for the army and government. It is also clear from the Lurgan, Magherafelt, and Laurel Hill robberies that while security measures and personnel screening in those days left much to be desired, the army and police were diligent in recovering the arms once taken. Regular security operations also helped to pick up some of the firearms, but many more remained at large and were used intensively: forensic reports showed that one of the Sterlings from the October ’72 Lurgan raid was involved in no less than 11 shooting incidents carried out by the UVF and RHC between then and June ’73. An SLR taken from the Royal Irish barracks in Ballymena in 1973 was not recovered for another 20 years. It had been fired over the coffin of Colin Caldwell, a UVF member killed by an IRA bomb in Crumlin Road Jail.

For all the criticism from republicans regarding the raids on army bases, the IRA did not turn down weapons from similar sources across the Atlantic. Between 1971 and 1974, 6,900 firearms and 1.2 million rounds of ammunition were stolen from military installations across the United States – far more than were ever taken from bases in Ulster by loyalists – with many of the thefts believed to have been carried out by IRA sympathisers. One raid on a National Guard armoury in Danvers, Massachusetts in 1976 seized, among others, seven M-60 belt-fed general purpose machineguns, which were later smuggled to the Provisional IRA. Two years later Gunner Paul Sheppard of the Royal Artillery became the first member of the security forces to be killed in an M-60 attack. The IRA also targeted UDR members for weapons, a fact seldom mentioned by Sinn Fein, although not nearly to the extent loyalists did. In one such incident at the farm of a part-timer near Rathfriland a PIRA unit stole an SLR and shot the man and his son in the legs. The Official IRA stole guns and uniforms from the home of Joseph Wilson, a Lisdown UDR man later shot dead by the Provisionals. Weapons were also stolen from the Irish Army, including a GPMG from Clancy Barracks in January 1973 which went on to be used in numerous attacks – including several attempts to shoot down helicopters – against the security forces in Northern Ireland.

The record shows that when loyalists overreached themselves the arms raids usually ended in failure. In the case of the two mammoth UDA heists all of the weapons were recovered within hours, while the UVF raid on Lurgan was only a partial success in light of what could have been. The practical issues of transporting and hiding such large amounts of weaponry, and the aggressive response from the security forces that these undertakings inevitably provoked were inimical to making a clean getaway. The two UDA operations could not be faulted for their planning or execution, but their very ambition sabotaged their chances of success. UVF hold-ups on the other hand tended to be less grand in scale, but they kept more of their gains.

Civilian Guns

“[…] nothing herein contained shall extend to authorize any Papist or person professing the Popish or Roman Catholic religion, to have or keep in his hands or possession any arms, armour, ammunition, or any warlike stores, sword blades, barrels, locks, or stocks of guns or fire arms, or to exempt such person from any forfeiture or penalty inflicted by any act respecting arms, armour or ammunition, in the hands or possession of any Papist, or respecting Papists having or keeping such warlike stories, save and except Papists or persons of the Popish or Roman Catholic religion, seized of a freehold estate of one hundred pounds a-year, or possessed of a personal estate of one thousand pounds or upwards, who are hereby authorized to keep arms and ammunition as Protestants now by law may … “

The raids on military facilities provided loyalists with quality firearms capable of matching most IRA weapons, but they required good planning and logistical backup. More importantly, they entailed a significant degree of risk – as the Magherafelt and Laurel Hill jobs showed, success was far from guaranteed. Another source exploited by the paramilitaries represented far less of a gamble in operational terms: the thousands of legally-held civilian firearms held by Northern Irish citizens.

The legal trade in arms continues to play a small but significant role in arming non-state actors in conflicts around the world. The quartermasters of Mexico’s narco-gangs for example have only needed to look across the border to find all the weapons they could ever need. The supply lines running from less-scrupulous gun dealers in New Mexico, Arizona, and elsewhere, supplemented by “straw purchases” where intermediaries purchase smaller batches, have led to a situation where American weapons form some 70% of all narco-gang arms, as evidenced by the large numbers of guns which have been seized by the Mexican authorities, ranging from automatic pistols and AR-15 derivatives, to Barrett and McMillan .50 calibre anti-material rifles capable of penetrating light armour.

The ownership of guns was a deeply contentious issue during the Troubles, particularly for nationalists and republicans, the roots of which can be traced back much further to the Penal Laws which began to be enacted in the late 17th century. In an effort to neutralise the threat to English and Scottish settlers, and to Great Britain itself, posed by the rebellious and discontent native Irish, legislation was introduced which barred Roman Catholics not meeting a property and financial qualification from owning swords or firearms. The laws were gradually repealed over the course of the 19th century, but disarmament at the hands of the Ascendancy proved to be a bitter and potent fragment of folk memory which played an important part in shaping modern republican attitudes towards legal Protestant-owned guns. In the endlessly protracted discussions over decommissioning Sinn Fein consistently made reference to the matter of these firearms when stating their desire for the removal of “all the guns” from Northern Ireland (meaning legally-held ones as well as those of the security forces). Further illustration of this viewpoint can be found in an article from this period by Ann Cadwallader. Writing in Ireland on Sunday, Cadwallader, now a researcher and activist for the Pat Finucane Centre, made use of a comically dramatic and overblown metaphor to relate nationalist fears:

[j]ust as during the Cold War, when the very existence of intercontinental ballistic nuclear missiles, lurking in silos in the USA and USSR, had the effect of bi-laterally limiting the military/political ambitions of both superpowers, so these legally-held weapons in the North have their own baleful effect.

The risk posed by dour Presbyterian farmers with thermonuclear arsenals in their haylofts notwithstanding, legally-held firearms were neither an operationally significant nor plentiful source for loyalists, but for the poorly-armed paramilitaries of the late 60s and early 70s anything which went “bang” was regarded as better than nothing. Raids were soon organised on gun dealers, shooting clubs, and the homes of those known to possess weapons. Potential targets were plentiful – in 1972 there were 296 registered dealers and 108 clubs in existence throughout Northern Ireland. A gun club based at the ICI plant in Kilroot was targeted in November ’72 by loyalists who made off with four .22 rifles and 200 rounds of ammunition. The armed four-man team held up the club’s lone security guard before loading the guns into a car and escaping. A young Michael Stone, at this time a member of the UDA, was ordered to acquire firearms by the organisation’s commanders:

We decided to rob a blacksmiths/gunsmiths in Comber. I would have been about 16 1/2. We burgled it. We only got five shotguns, .22 rifles, Remington pistols and .303 ammunition. We took it to a ‘hide’ on the outskirts of the Braniel.

Stone was later arrested for the robbery, denied all paramilitary involvement, and received a six-month sentence.

In the same period raids were also taking place outside Northern Ireland. Over the border in Co Louth, loyalists stole 40 assorted firearms from a gun shop and gunsmiths in Drumiskin. The UVF and UDA were also at work across the sea in Scotland. In July ’73, on the same day that the army swooped on Gerry Adams and over 20 other senior leaders in the Provisional IRA, UVF volunteer Danny Strutt was arrested at Larkhall Orange Hall in south Lanarkshire. A search of the premises uncovered 15 rifles and 2300 rounds of ammunition which he had recently stolen from Greenside Rifle Range in Edinburgh. A year earlier Strutt had made a dramatic escape from Crumlin Road jail by sawing through the bars of his cell, disguising his absence with a dummy complete with painted papier mache head and wig (made from his own hair) in his bed.

Nationalist concern over the growing number of thefts targeting guns shops, clubs, and owners led to a major debate on gun control which dominated the second half of 1972. It came to a head in October when leader of the opposition Harold Wilson opened his speech at the Labour Party conference in Blackpool by calling for a total ban:

Must our troops be subject to a virtually uncontrolled gun-law? On April 6, 1971, 18 months ago, in the anxious debate which followed the deposition of Major Chichester-Clark and the accession of Mr Faulkner, I demanded that all gun licences be withdrawn, subject to a minimum issue for self-defence in remote areas, including the border. I demanded that, these apart, the holding of private weapons be no longer tolerated in Northern Ireland. There are upwards of 100,000 licensed weapons in Northern Ireland, and God alone knows how many illegal ones. I now warn Mr Heath. The possession of private arms is not an inalienable human right. Public opinion in Britain will not for long tolerate the continued presence of British troops, unless firm action is taken to make illegal the holding of private arms.

Compared with the surfeit of Armalites, sub-machineguns, and other weapons swamping Northern Ireland at the time legally-held firearms constituted a small and not particularly formidable threat, but Wilson was keen to take up the concerns of the minority community and outmanoeuvre the government on the issue. William Whitelaw pointed out that no member of the security forces was known to have been killed with a legally-held gun at that point, although the situation regarding civilians was less clear.

The Lynch government in the Republic had already mounted the preventative call-in of all handguns, and rifles over .22 calibre, they along with shotguns being exempted, as pressure mounted for the authorities further north to follow suit. A Belfast magistrate speaking after the prosecution of one FAC holder for exceeding his allowance stated “it is time everyone looked at everyone’s firearms certificates in this country. Another country has decided to call in certain arms”. Anti-gun sentiment gained momentum and the Belfast Telegraph reported “Legal arms in Ulster may be banned”. The paper threw its weight behind calls for a ban, an editorial declaring “the general public would breathe more easily if Mr Whitelaw ordered all civilian-held guns to be turned in immediately, and all gun clubs to be disbanded, for the sake of public safety”. Wilson’s proposals also found immediate support from the SDLP and Provisional Sinn Fein.

Adding its voice to the debate around civilian arms was the Catholic Ex-Servicemen’s Association. A statement released following a meeting of the group in Lurgan let it be known that:

the Association expressed great concern regarding the continuing policy of allowing licensed guns to remain in the hands of over 100,000 people in Northern Ireland. They question the right of these 100,000 people to have a means of protection when a further 1 1/2 million people in Northern Ireland have no such right. What entitles them to the privilege of being armed other other than that they are, in the main, Unionist Government supporters?

Although plainly paramilitary in nature – members wore uniforms of a fashion and conducted street drills – the CESA, a legal group of some 8,000 members led by chairman Phil Curran, a former soldier himself, claimed that it neither possessed guns nor carried them during its “defensive” vigilante patrols. In reality the group was armed to a certain degree, even if guns were not displayed openly. In November 1972 a 27yr old Dunmurry man was jailed for four years at a court in Belfast for unlawful possession of five rifles, two shotguns, and 350 rounds of ammunition with intent to endanger life. The ex-soldier, described as a “weapons training officer” in the CESA, had moved to Northern Ireland from England and converted to Catholicism after marrying a local woman. The court heard how he had smuggled the guns into the Bogside and given training lessons to people who were “not members of the CESA” – a veiled reference to the IRA. In fact the CESA regularly gave training to IRA volunteers. Following the trial the organisation was criticised by the Alliance Party in west Belfast who said, “[the] CESA has been in existence for some time now, and the only noticeable change in Catholic areas attributable to them is the rash of illegal drinking clubs […] the only reason for such a force is to give Mr Curran the satisfaction of having the same petty and illegal power as Tommy Herron of the UDA”.

Gun owners reacted angrily to talk of a ban, claiming that any law would unfairly and disproportionately affect rural Protestants and leave them at the mercy of an IRA well-armed with illegal guns, with George Green of the Ulster Special Constabulary Association heading up criticism. The Belfast Telegraph printed a copy of a letter sent to Wilson by an anonymous shooter writing under the name “Sportsman”:

I am quite appalled at your attitude towards legally-held guns which, as you must appreciate, are in the hands of sportsmen. I can appreciate that the present situation in Northern Ireland could cloud personal judgement but I can see only political opportunism in your recommendations to Mr Paul Channon in the House on 31st July 1972, to impound all privately and legally held guns in our province […] even the most naive person must appreciate that even if all legally-held guns were impounded, the illegal rifles, revolvers and explosives would still be in profusion, and it is these which are taking human life […] remember that the authorities know where the legal guns are; it is the illegal guns they have to worry about.

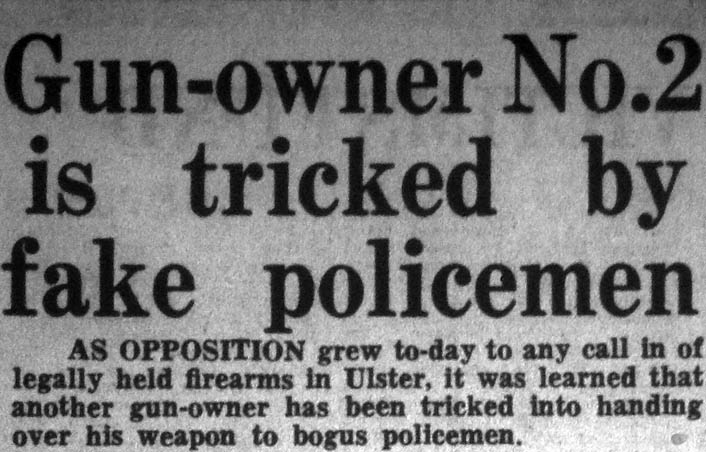

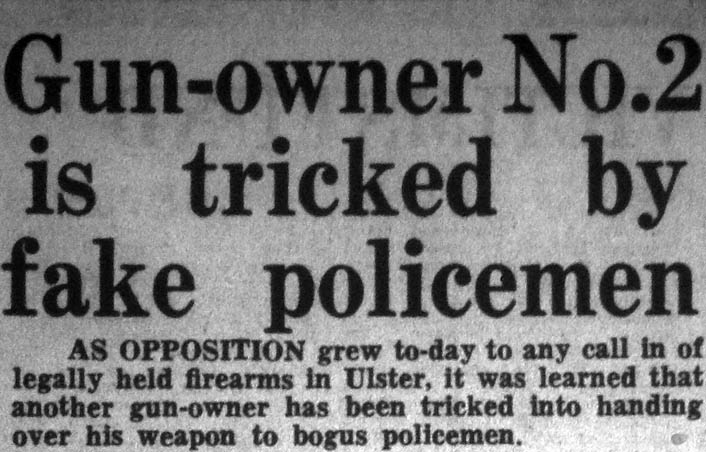

In the end only 1,000 fullbore rifles were called in to be held in gun clubs with fortified stores. The debate had an unexpected side effects as the UVF deviously took advantage of confusion over the law. Two men posing as police officers enacting a call-in of legal arms came to the door of a gun owner in Templepatrick and tricked him into handing over a licensed weapon. A week later in Glengormley they succeeded in taking a shotgun using the same ruse, even giving the owner a receipt for the gun. As a result of a number of such deceptions the RUC were forced to issue a statement reiterating that no call-in had been ordered. The more confrontational robberies that were also taking place at this time were not without risk. An attempt by two loyalists, one armed with a revolver, to steal weapons from a licensed owner living off the Albertbridge Road was foiled when the man opened fire on them with a shotgun.

How important were legal civilian-owned guns as a source for the loyalist paramilitaries? The evidence suggests “not very”. Nationalist claims of upwards of 140,000 firearms in circulation were incorrect. In 1972 the figure actually stood at roughly 77,000 certificates covering 106,000 weapons of all kinds: 93% of these were shotguns (73,160), .22 rimfire rifles (13,767), or airguns (12,125). The militarily-worthless airguns were not, are not, subject to license in Great Britain, leaving a total figure of 92,926. Neither remaining category constituted a particularly formidable resource: 281 shotguns were stolen from private owners in 1972 and ’73 but they lacked range, ammunition capacity, and without buckshot or solid shot, hitting power; .22LR rifles suffered similar disadvantages and were less than a tenth as powerful as an Armalite. Many of the stolen guns were stashed away in long-term hides in rural Antrim and Down for issue in the event of a “Doomsday” united Ireland scenario. Even then it is doubtful whether they would have been of much benefit beyond a simple morale-booster. The experience of the Confederacy during the American Civil War proved that shotguns are a poor substitute for military firearms.

More useful were the 6,520 legally-owned handguns, of which 2,800 or roughly 40% were Personal Protection Weapons owned by members of the security forces. By 1978 and in the face of mounting attacks on vulnerable off-duty personnel that figure had increased to 7,550. Northern Ireland was not subject to the ban on handguns enacted by the Tory and later Labour governments in response to the Dunblane massacre of 1996, and while up to date figures are not available it is believed thousands of PPWs are still held by serving and former members of the security forces and prison service. Politicians, contractors to the security forces, and other figures seen as potential targets for assassination were also granted PPWs. Even Sinn Fein, in spite of its usual hostility towards legally-held firearms, called for its members to be permitted licensed guns for their protection in August 1993 after scores of loyalist attacks.

The standard PPW for members of the UDR in the early days was the .22LR Walther PP automatic pistol, adopted by the MOD as L66A1 at a cost of £155 each. It was not a popular choice – although concealable its hitting power was regarded as pathetic and its rimmed cartridge was not conducive to reliability, leading many to purchase more powerful guns at their own expense. Later it was replaced by the far superior Walther P5 in 9mm Parabellum. All the same, loyalists attempted to steal the little PPs whenever the opportunity presented itself. Typically an off-duty UDR man would be identified in a bar and waylaid on the way out once he was the worse for wear. Violence was sometimes used. In 1981 David Smyth, a 24yr old Protestant from Highburn Gardens, was stabbed to death in an bungled mugging when a UVF/RHC gang tried to take a PPW from his companion, a member of the UDR, as they left a UDA-run drinking club. The off-duty soldier had drunkenly fired his gun in the air minutes before the attack.

Politicians have frequently turned to gun prohibition as a quick-fix solution to violence or in response to political crises. Fear of socialist revolution in the years following the First World War prompted the UK’s first real firearms legislation and registration. Aside from the call-in of fullbore weapons held for sport and hunting there was little else the government – well aware that it was the illegal shipments of military-grade weapons flowing into the country which were really fuelling the violence – could do in this area given Northern Ireland’s already strict gun laws.

Even had a blanket ban been enacted loyalists would still have been able to equip themselves through raids wherever guns were kept. The lengths they were willing to go to, and the eclectic nature of the sites they targeted in their search for arms, are clearly demonstrated in the daring UVF raid on the government forensics laboratories in Belfast in early 1973.

Forensics labs were a vital and integral component in the security force’s fight against both loyalist and republican terror groups. It was there that spent ammunition cases and bullets unearthed from crime scenes and removed from the bodies of shooting victims would be expertly examined, catalogued, and cross-referenced against an index of previously-recovered examples to identify both the weapon used and the possible perpetrators. Articles of clothing were also held for analysis to detect traces of explosives and gunshot residue. The work of such labs had been instrumental in jailing countless active members of the UVF, UDA, and IRA over the previous four years.

At around 2am on Saturday the 31st of March a large number of UVF men – the exact figure is unknown, but as many as 10 cars are believed to have been involved – breached security at the Belfast headquarters of the Department of Forensic and Industrial Science on Newtonbreda Road. Surprisingly, this was not a difficult task in itself: in spite of the fact that it held a vast quantity of lethal weaponry and ammunition the building had no police or army sentries and the alarm system was not functioning, while the civilian security guards protecting the premises were easily overpowered and tied up. Having made it inside, the UVF got to work. Over the next few hours it worked methodically and selectively through the labs collections, leading the RUC to believe that the raiders were well-prepared and knew what they were looking for.

Roughly 100 firearms and an unspecified amount of ammunition were taken, including SLRs, Armalites, M1 carbines, handguns, Thompsons, and other sub-machineguns. Various articles of clothing relating to upcoming UVF trials were also stolen. But the biggest coup of the night was the theft of an RPG-7 rocket launcher originally seized, like many of the other weapons, from the Provisional IRA. This was militant loyalism’s first encounter with the RPG, many years before the Lebanon and Teesport shipments, but unfortunately for the UVF no rockets were to be found. Years later, the Joe Bennett supergrass trial heard that John Bingham was specifically tasked with sourcing a supply of rockets from contacts in the US and Canada, which he succeeded in doing.

The raid was front-page news in the Belfast Telegraph and Newsletter the following Monday. William Whitelaw immediately called a meeting of his security committee to discuss the raid, with Army GOC Sir Frank King, RUC Chief Constable Sir Graham Shillington, and the laboratory’s director Dr John Howard in attendance. Such an audacious theft from an important facility was deeply embarrassing to the government. Indeed, so outraged were they that the Deparment of Commerce, which had responsibility for the labs, placed a ban on the release of information to the press regarding the robbery. In the absence of any details the raid soon faded from the public consciousness and today is virtually forgotten, in spite of it being one of the most successful instances of loyalist “self-service”.

In the wake of the lab raid a number of court cases fell apart, no doubt as the UVF had intended, but not all of the consequences were positive from their perspective. Just a week after the hold-up the trial of a Dungannon republican held for possession of a Thompson SMG and a full magazine of ammunition collapsed after prosecution lawyers informed the judge that the exhibit had been stolen from the forensics HQ.

But there was one more source of arms that loyalists raiders targeted, a source which has not been explored in detail but which illustrates better than any other the extreme measures which were resorted to in order to equip the UVF and UDA…

Eating the IRA’s porridge: raids on republican arms dumps

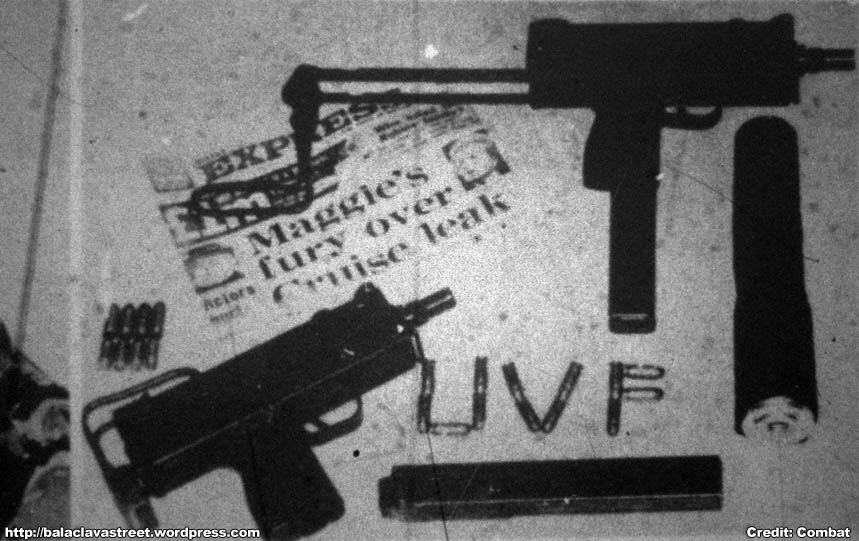

July 1972: a member of the UVF poses with an AR-18 stolen from the IRA

“The guerilla soldier must never forget the fact that it is the enemy that must serve as his source of supply of ammunition and arms”

Che Guevera

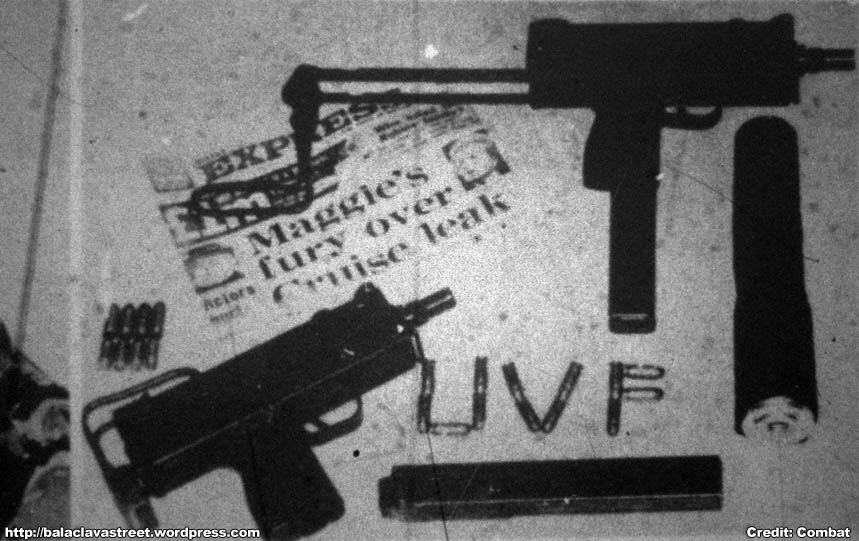

At the beginning of August 1972 the Northern Ireland press reported that the UVF had obtained a quantity of Armalite AR-18 assault rifles. This compact, high-velocity, rapid-firing weapon, easily capable of penetrating the soft American-type body armour then worn by British troops in theatre, had already become notorious in the hands of republican gunmen. Publishing photographs of masked UVF members wielding the rifles, the press speculated that the organisation had received a consignment of them from the US, or possibly Japan where they were produced by the Howa Armaments Company under license from Armalite. They had not. They had stolen them from the IRA.

Raids on IRA arms dumps remain a sensitive and poorly-understood aspect of loyalist arms procurement. It is beyond doubt that they occurred, but the scale and frequency of forays to seize “enemy” supplies as a source for the UVF and UDA is something that has still to be established.

Sorties to capture each others arms dumps were certainly a regular feature amongst the rival Provisional and Official wings of the IRA, and later the INLA, in the 1970s. According to Brendan Hughes’ testimony to Boston College’s Belfast Project, the Provisional IRA stole a consignment of image-intensifying night sights from the Officials. One member of the INLA in its early PLA guise was kneecapped by the Officials for stealing a gun from one of its dumps.

The best accounts of this phenomenon on the loyalist side come from the UVF. One member of the organisation I spoke with, who was not involved in the raids but is well-informed regarding all aspects of the UVF’s history, said that while raiding IRA arms dumps probably did not constitute a major source of guns, it could be understood as having a moral benefit quite superior to any material gain. Demonstrating that “[the UVF] can go into your areas and take your guns” was potentially a powerful message to the group’s republican enemies, showing that they could penetrate nationalist strongholds, even no-go areas, to strike at will. Another source informed me that loyalists employed as workmen for Belfast Corporation made a point of routinely searching homes in republican areas they were called upon to repair, to check for weapons caches which might be pilfered at a later date.

Violent takeover-style robberies of TA and UDR depots were a potentially hazardous undertaking at the best of times, but stealing weapons from under the nose of a watchful and ruthless IRA which would not hesitate to execute any loyalist interloper caught with his arm beneath the floorboards elevated the risk to an even greater level. The scant documentary accounts of this practice do indeed testify that it was not without repercussion. In May 1972 the UVF looted an OIRA arms cache being stored in a house off the Antrim Road. The furious Officials responded by abducting three Shankill Protestants stopped at one of their illegal checkpoints in Turf Lodge while driving to work along the Monagh Road. The men were taken to an OIRA “call house” and kept in a coal cellar where they were interrogated about the theft. After three hours the Officials released them. In another incident the OIRA snatched three loyalists from South Belfast. This episode would lead to a celebrated, albeit arm’s-length, encounter between Gusty Spence and the legendary Official IRA figure of Staff Captain Joe McCann. As Spence related to Roy Garland:

There were Official IRA armaments held in a house in north Belfast. The UVF knew about this and the guns were taken and passed over to the organisation. The Official IRA then swept into Sandy Row and lifted three fellows. They then released one man, saying, ‘Tell the UVF that if we don’t get these guns back we’re going to shoot these two fellows’. Through my contacts I was told that the two fellows were not UVF men although the man they released was. I sent word to Joe McCann, ‘Joe, you’d be shooting them for the wrong reasons. Don’t do it. Do me a turn and I won’t forget about it’. One Official IRA man wanted to shoot them dead but Joe released them, a magnanimous gesture.

In the early summer of 1974 Combat magazine carried reports of another raid. The piece alleged that:

As a result of information received from the Security Forces [emphasis mine], a Unit of the Mid-Ulster Volunteers seized a quantity of weapons from what is believed to have been an IRA arms dump.

The Unit captured a Thompson sub-machine gun, two revolvers and a quantity of ammunition and explosive materials. Before leaving the ‘dump’ the Unit laid a booby-trap mine which later exploded causing injury to an IRA quartermaster. In a report to Brigade Staff, the Officer Commanding the 3rd (Mid-Ulster) Battalion said that this had been the third successful arms seizure in the Tyrone area within the past month.

While the purported blowing up of an IRA quartermaster with a booby-trap reads like embellishment – I have not been able to confirm it thus far – the claim that the Mid-Ulster UVF raided a republican arms dump after a tip-off from a sympathetic – or infiltrated – source within the security forces is credible.

After the UVF’s successes in robbing republican arms dumps their recently-formed rivals in the UDA were keen to get in on the act. On the 6th October 1972 the front page of the Belfast Telegraph carried a statement from the UDA which said that a “commando team” had crossed over the border into Co Monaghan and raided IRA arms dump. Claiming to have captured a number of Armalites and a quantity of explosives, a UDA spokesman said:

While Lynch refuses to take stern action against the terrorists we feel we have no alternative but to continue our raids. As terrorism increases here in Northern Ireland we will step up our activities in the Republic.

It followed repeated threats from the organisation to carry out punitive operations across the border. The Gardai Siochana said that their patrols in the area had not noticed any unusual activity, while Cathal Goulding of the Official IRA claimed that the first he had heard of the raid was on the morning radio. Nor did the UDA put any of the alleged arms on display – although there was some debate about whether to hand them over to the army – but some time later weapons usually associated with the republican paramilitaries began appearing in the hands of UDA operators. The M1 carbine used by a UDA gunman to shoot and badly wound Charles Harding-Smith on the Shankill during an internal dispute was usually regarded as a signature IRA weapon, particularly of the Official wing, although the UDA had possibly received a small number of them from supporters in Canada.

Rattlers, Shipyard Specials, and Widowmakers: loyalist homemade firearms

Loyalist homemade Sten-type sub-machinegun. Credit: Imperial War Museum.

The urban guerrilla’s role as gunsmith has a fundamental importance. As gunsmith he takes care of the arms, knows how to repair them, and in many cases can set up a small shop for improvising and producing efficient small arms […] homemade weapons are often as efficient as the best arms produced in conventional factories

Carlos Marighella, Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla